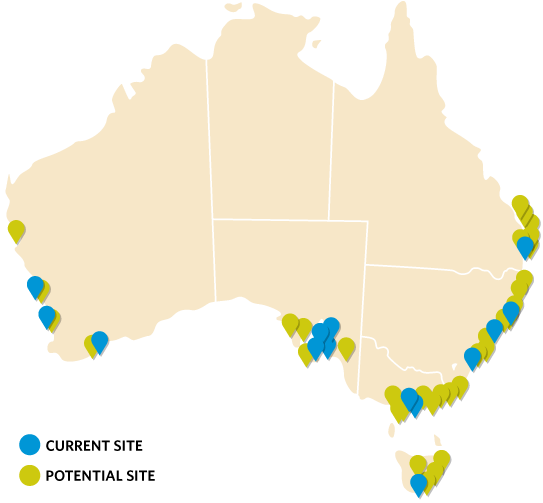

Since the arrival of European settlers, shellfish reefs that once spanned from Noosa, Queensland around Australia’s southern coastline to Perth, Western Australia, have now all but disappeared.

There are now less than 10 per cent remaining. And it’s a problem.

Why? Because healthy shellfish reefs have multiple benefits for land, sea, and culture. Oyster beds:

- Act as grounds for nursery, foraging, hiding, and resting for local fish populations.

- Are important habitats for invertebrates, fish and birds, some of which are considered threatened or critically endangered.

- Alongside, shellfish reefs also improve water clarity by removing nutrients and pollution from the water and as very sturdy reefs, they help protecting adjacent habitats and our coasts from erosion.

We need to protect and recover this critically endangered ecosystem.

That’s why we’re leading Australia’s largest marine restoration initiative, to bring shellfish reef ecosystems back from the brink of extinction — for the benefit of both people and nature.

Together with governments, businesses, and the community, we aim to protect and restore 60 shellfish reefs across Australia – including Botany Bay – in a world-first attempt to recover a critically endangered marine ecosystem.

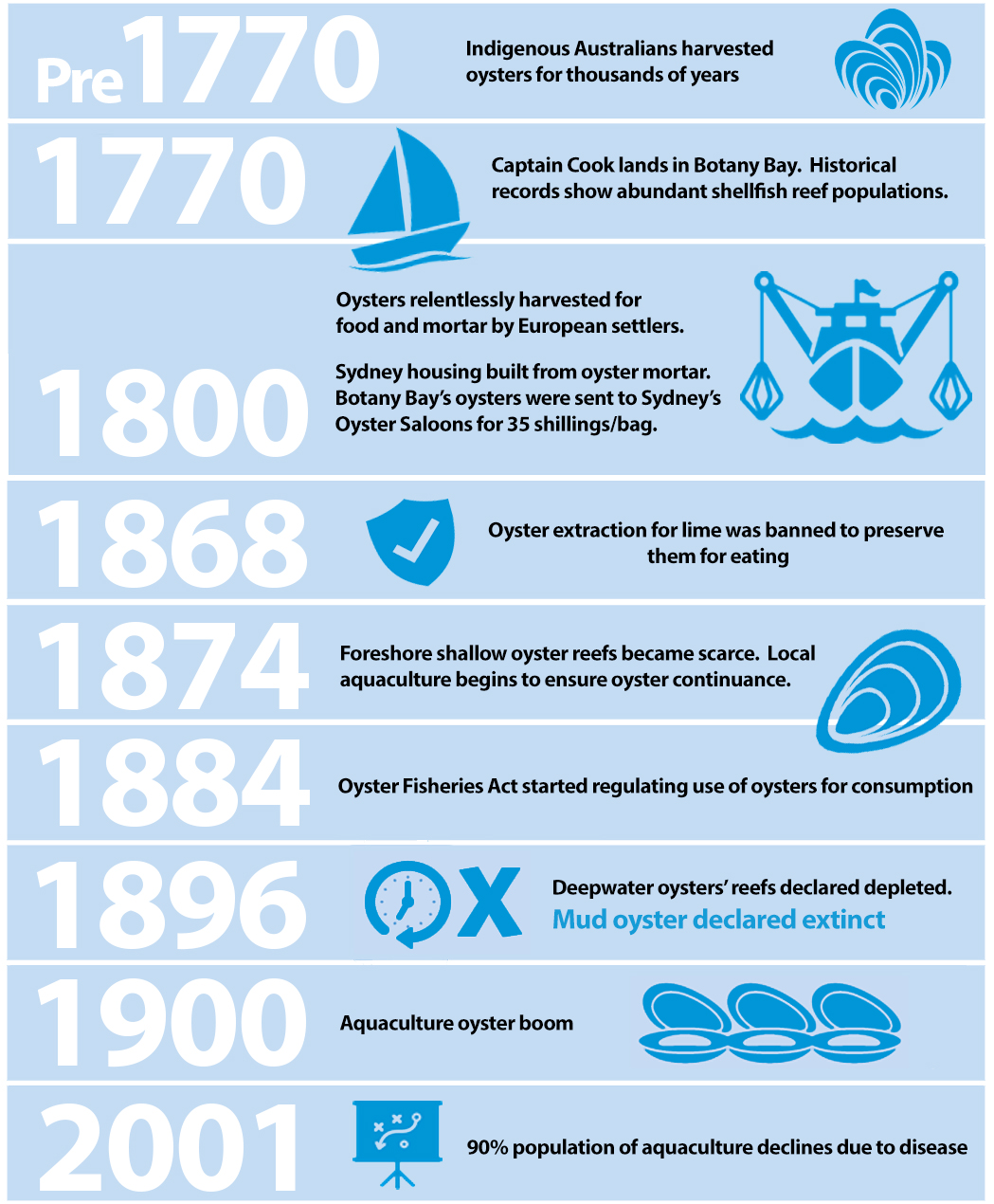

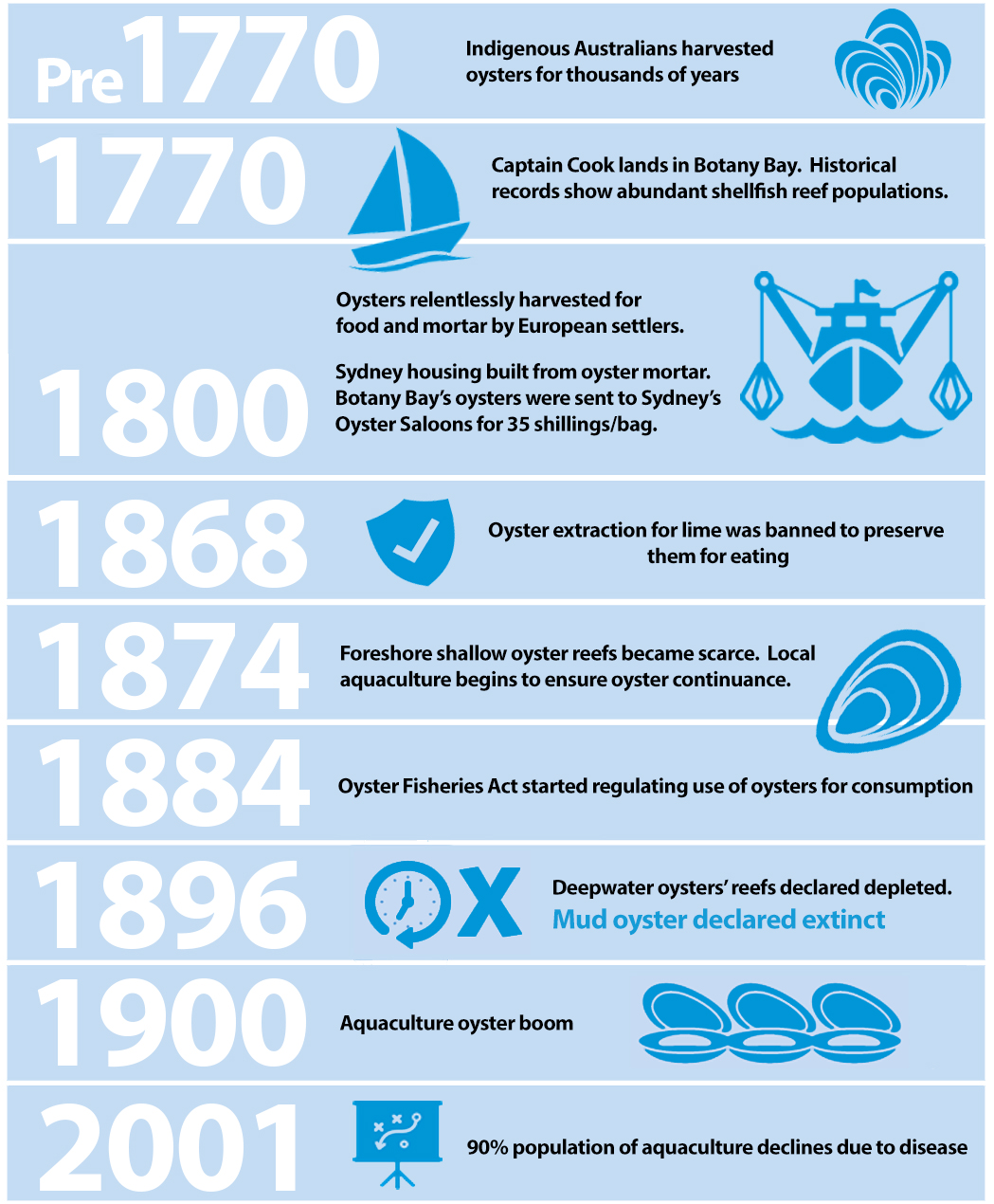

Indigenous Harvests

Botany Bay is one of Australia’s most well-known landmarks, but its cultural significance extends far beyond the 1770 landing of the First Fleet.

Named Botany Bay by Captain James Cook for its “great quantity of plants”, the region known as Kamay in Dharawal dialect was a place of shallow waters and extensive shellfish reefs.

Once the dominant feature of many NSW estuaries, it’s widely known that shellfish provided a sustainable source of protein for local Aboriginal people. Middens containing native oyster shells found along the Cooks River and lower Georges River prove that local Aboriginals collected and ate shellfish and crustaceans for thousands of years prior to colonisation.

Despite the significant scale of consumption over time, the impact of Aboriginal farming was relatively gentle. In fact, in some areas, Aboriginal people were able to enhance the oyster beds thanks to their intimate knowledge of sea country and aquaculture.

Oyster beds were also an important location for cultural gatherings and shells were used in toolmaking.

Quote: John Hawkesworth

About the head of the harbour, where there are large flats of sand and mud… On these banks of sand and mud there are great quantities of oysters, mussels, cockles, and other shellfish.

The Rise of Aquaculture

As European settlers journeyed into Sydney Harbour, they had to navigate a coastline literally encrusted with oyster reefs.

With a growing need for nutritious food, oysters were initially harvested from natural reefs. Oyster shells were also used as the key ingredient for mortar, before lime was discovered west of the Blue Mountains.

Early colonial buildings – the first Government House, Hyde Park Barracks, and Vaucluse House – were built with shelly mortar produced from burning oyster shells gathered from both middens and living oyster beds. (This practice was eventually banned by the government in 1968 to preserve oysters for consumption.)

With dwindling natural stocks, oyster cultivation in the Georges River became one of Australia’s first aquaculture enterprises. By 1886, commercial oyster farms were managed successfully in the region and remained in operation for almost 100 years.

In Botany Bay though, the Native flat oysters (also known as mud oysters in this era) were declared extinct by 1896.

Quote: Captain James Cook

I went […] to sound and explore the Bay, in the doing of which I saw some of the Natives; but they all fled at my approach. I landed in two places, […] here, likewise, lay vast heaps of the largest oyster shells I ever saw.”

Disease and Depletion

By the early 1970s, the Georges River boasted one of the most productive oyster industries in NSW. But it didn’t last.

Population increases along the Georges River and consequent runoff, degraded local estuaries, impacting oyster cultivation. In the late 1970s, over 2,000 people got food poisoning after heavy rainfall caused pollutants from sewage and stormwater to overflow into the estuaries.

Pollutants continued to impact productivity throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, and ongoing disease from the mid-1990s to 2010 mean only a few oyster farms survive in the Georges River today.

We’ve Got Hope for the Future

It may not be time to shell-ebrate just yet, but there is hope.

The natural populations of Sydney rock oysters are showing signs of good health and resilience with improving water quality, the introduction of eco-friendly fishing practice, improved sewage regulations, and land reclamation. These promising signs of recovery were key in kick-starting the first shellfish reef restoration project in Botany Bay and the Georges River in order to assist with the recovery of remnant Sydney rock oyster reefs and the bold commitment of re-introducing the Native flat oyster reefs to its previous habitat range.

With successful reef restorations in Victoria’s Port Phillip Bay and Adelaide in South Australia, we’re committed to bringing shellfish reefs in Botany Bay and the Georges River back from the brink of extinction as part of the national Reef Builder initiative.

You can help us restore shellfish reefs across AU

Just $75 could buy 2,500 baby oysters to stock our reefs

DONATE NOW