Key Takeaways

Urban green spaces generate enormous economic, environmental and public health benefits in cities.

Green spaces are threatened in many cities as development eats away at natural areas and climate change makes the environment inhospitable to native flora.

Melbourne, Australia has developed a greenprinting strategy that brings together diverse stakeholders to conserve, expand and connect urban greenspace on a metropolitan scale.

With a screeching flash of red and blue while you’re enjoying your first morning latte, urban nature comes to brilliant life in suburban Melbourne. Whether a Crimson Rosella, a Superb Fairy-wren, or a Sulphur-crested Cockatoo, the showy birds that rely on urban trees and parks are part of the city’s culture.

“We’re blessed with a rich array of incredible birds in Melbourne,” said James Fitzsimons, Director of Conservation for The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in Australia. “It’s very special to be able to regularly see and hear beautiful birdlife in our big city.”

Melbourne, located in the southeast corner of Australia, is consistently lauded as one of the world’s most “liveable” cities in the world. But what does that mean? Sure, it’s renowned for its laid-back Aussie lifestyle, its lively cafe and arts culture and its passion for all things sport, but there’s one more essential element: nature.

Melbourne has more than its fair share of parks, public and private gardens, and leafy thoroughfares—in fact, about 19 percent of the metropolitan area is devoted to green space. And all that greenery does more than just make the city beautiful; it makes Melbourne a healthier environment for both people and nature.

To protect and enhance these natural assets, Melbourne has become one of the first major cities in the world to develop a plan for nature at a metropolitan scale—a process called “greenprinting.” Importantly, the plan has three goals: to protect human health, nurture abundant nature and strengthen natural infrastructure.

Birds of Melbourne

What is greenprinting?

Greenprinting is the process of developing a conservation strategy that documents the environmental, economic and social benefits that trees, parks, working lands and other types of green space provide to communities.

“We’re all familiar with the concept of blueprints for planning buildings and streetscapes but here we’ve created a greenprint for all of Melbourne—a plan for protecting and enhancing an urban forest for an entire metropolitan area,” said Pascal Mittermaier, Managing Director of Global Cities at TNC. “Our greenprint for Melbourne is massive in scale and outstanding for its collaboration and use of new and innovative mapping technology.”

TNC believes greenprinting represents the kind of planning and cooperation required if we are to build truly sustainable cities that people and nature need, and Melbourne could set an example for cities around the world of how to get it right.

Quote: Joel Paque

Here we’ve created a greenprint for all of Melbourne—a plan for protecting and enhancing an urban forest for an entire metropolitan area.

Urban forests benefit nature and people

The abundance of birds and other urban wildlife that Fitzsimons enjoys in Melbourne comes from having a healthy urban forest—all the plants, big and small, within a city. And Fitzsimons would know, because like many Melburnians he lives in the outer suburbs and commutes to central Melbourne each day for work.

“I’m really lucky that I get to enjoy a very pleasant walk to the train station each morning in my appropriately named suburb of Ferntree Gully. But even once I disembark in central Melbourne there are still plenty of trees and shrubs on the streets and in the parks, even close in to the city centre.”

This wealth of vegetation didn’t come by accident. The fact is Melburnians really love their trees, as the recent proliferation of love letters from Melburnians to those trees attests. And well they might, because thriving urban nature means healthier urban people, a fact corroborated by extensive TNC research.

What’s more, the many services urban trees provide may come as a bargain: a recent study by the US Forest Service and the University of California found that every US$1 spent on tree planting and maintenance in Californian cities brought US$5.82 in benefits.

The benefits of trees

While urban trees and shrubs of all kinds can benefit nature, native species bring the most benefit for wildlife. TNC Chief Scientist and keen bird watcher Hugh Possingham explains: “Many Australian cities still contain a surprising diversity of wildlife especially in places where native plants—either in reserves or in people’s gardens—provide the right kind of habitat. So whether it’s a black cockatoo in a Perth backyard, a flying fox in a Brisbane fig tree or a fairy-wren in a Melbourne park, you can still encounter many native Australian animals thriving in our cities.”

Threats to urban greenspaces

But in Melbourne, as elsewhere, these liveable-city qualities are under threat.

With a population of eight million people projected by 2050, Melbourne will soon overtake Sydney as the biggest city in Australia—one of the world’s most urbanised countries. And typical of Australian urban areas, Melbourne has low levels of population density. The current population of 4.8 million people cover an area of approximately 2,000 square kilometres. That’s 2,400 people per square kilometre compared to 10,430 people per square kilometre for New York City, for example.

This preference for low density living is appealing for some residents but it also creates some challenges, including the efficient provision of services like utilities, and a larger physical footprint—which means ever more natural vegetation needs to be cleared or farmland lost for a growing human population.

Changes in urban form within that footprint are also contributing to the decline of Melbourne’s urban forest. A trend towards building larger houses on smaller greenfield lots in new suburbs, and urban infill in established urban areas, has led to reduced lawn and garden size and increased impervious surfaces like paved areas and roofs.

On top of all this, the changing climate brings higher temperatures—especially in urban areas—and lower rainfall, making it harder for trees in urban areas to thrive.

And with the climate continuing to change and the increasing urban sprawl, the decline in the urban forest is likely to increase in pace unless something is done to reverse the decline in tree canopy cover.

“Melbourne needed a plan to reverse this current and predicted future tree decline and sustain Melbourne’s liveability for people and nature,” said Cathy Oke, Councillor for the City of Melbourne. “If we are to protect our existing urban forest and enhance it into the future so that the people and wildlife of Melbourne can always enjoy it, we have to have a coordinated, connected-up strategy to manage it across the entire metropolitan Melbourne area.”

Creating an urban forest strategy

With this challenge in mind, TNC and Resilient Melbourne (part of the 100 Resilient Cities movement) came together to develop an urban forest strategy for the Melbourne metropolitan area in 2017. That complex task became the full-time responsibility of Martin Hartigan, TNC Australia’s Urban Conservation Manager.

“We needed to bring together 32 separate metropolitan councils (municipalities), multiple state government agencies and many other partners united around a common vision for our urban forest,” recalled Martin.

That agreed-upon vision became “our thriving communities are resilient, connected through nature.” It also became the guiding philosophy for a bold new strategy to create and maintain a greener, even more liveable Melbourne into the future: Living Melbourne: our metropolitan urban forest.

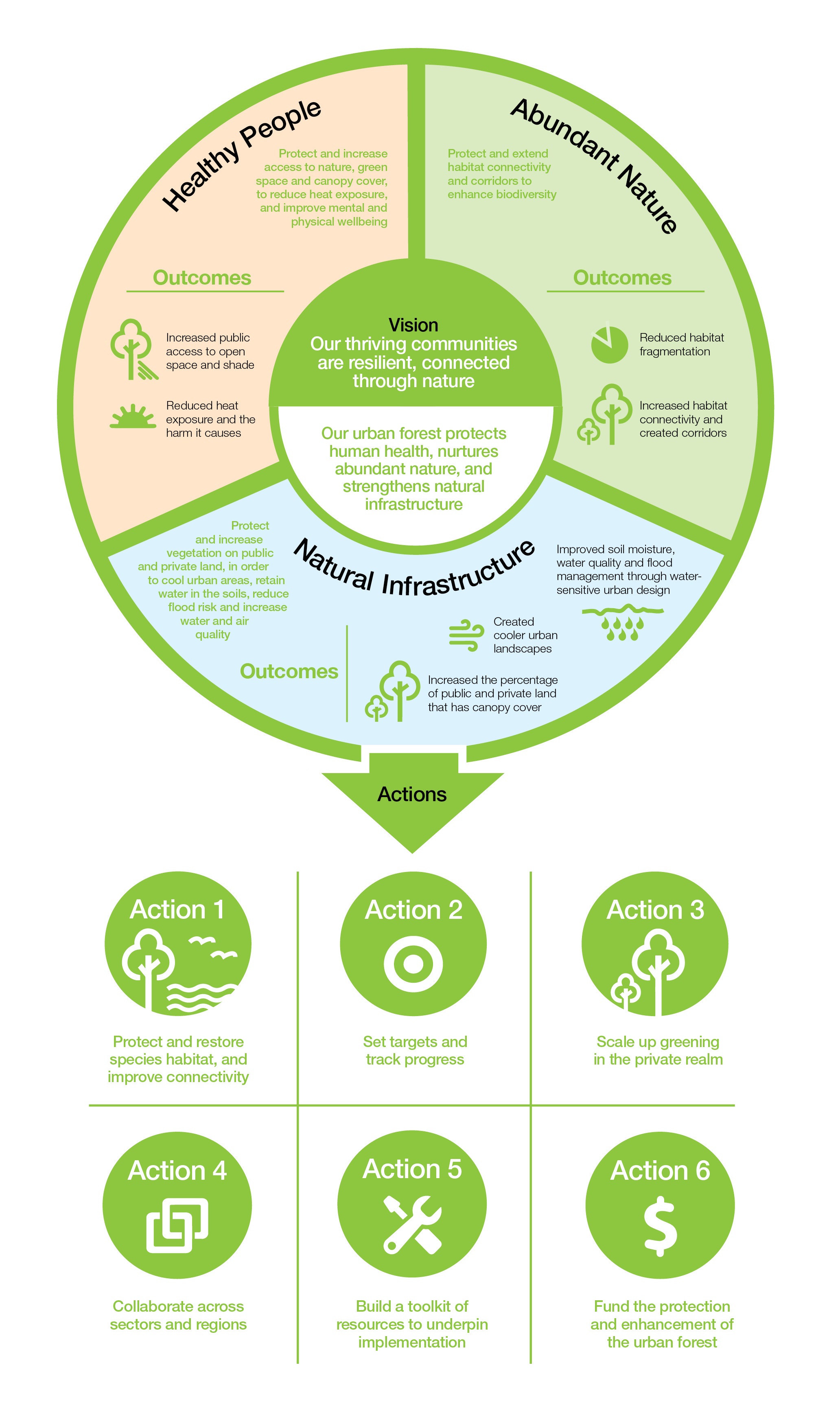

Living Melbourne has three main goals:

1. Healthy people: Protect and increase access to nature, green space and canopy cover to reduce heat exposure and improve mental and physical wellbeing

2. Abundant nature: Protect and extend habitat connectivity and corridors to enhance biodiversity

3. Natural infrastructure: Protect and increase vegetation on public and private land, to cool urban areas, retain water in the soils, reduce flood risk and increase water and air quality

Strategy framework & actions

“A lot of valuable work is already being done by Melbourne’s many different councils, the Victorian State Government, non-government and community organisations and private landowners,” said Maree Grenfell, Acting Chief Resilience Officer at Resilient Melbourne. “What has been missing until now is a way for this work to be coordinated, connected and supported at a metropolitan-wide scale. By working in partnership with TNC and all the other stakeholders we’ve been able to align existing work and commit to and inspiring future vision, together.”

Living Melbourne sets out six key actions as the way forward so we can combine the efforts of all the interested parties to realise the vision of thriving communities that are resilient and connected through nature.

Different cities have their own local ecosystems, of course—as well as their own unique threats to protecting those ecosystems. But the methodology used to create Living Melbourne could be replicated for any major city in the world, says Mittermaier.

"We think we can take this example of greenprinting and apply it to other major global cities so that they too have a strategy to protect and enhance their urban environment.”

Resources

Want to know more?

Email is the easiest way to find out how we're helping to conserve Australia's iconic natural landscapes and crucial wildlife habitats.

Global Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.