Investing our way out of the global water crisis

How finance, farming and freshwater conservation are becoming increasingly connected

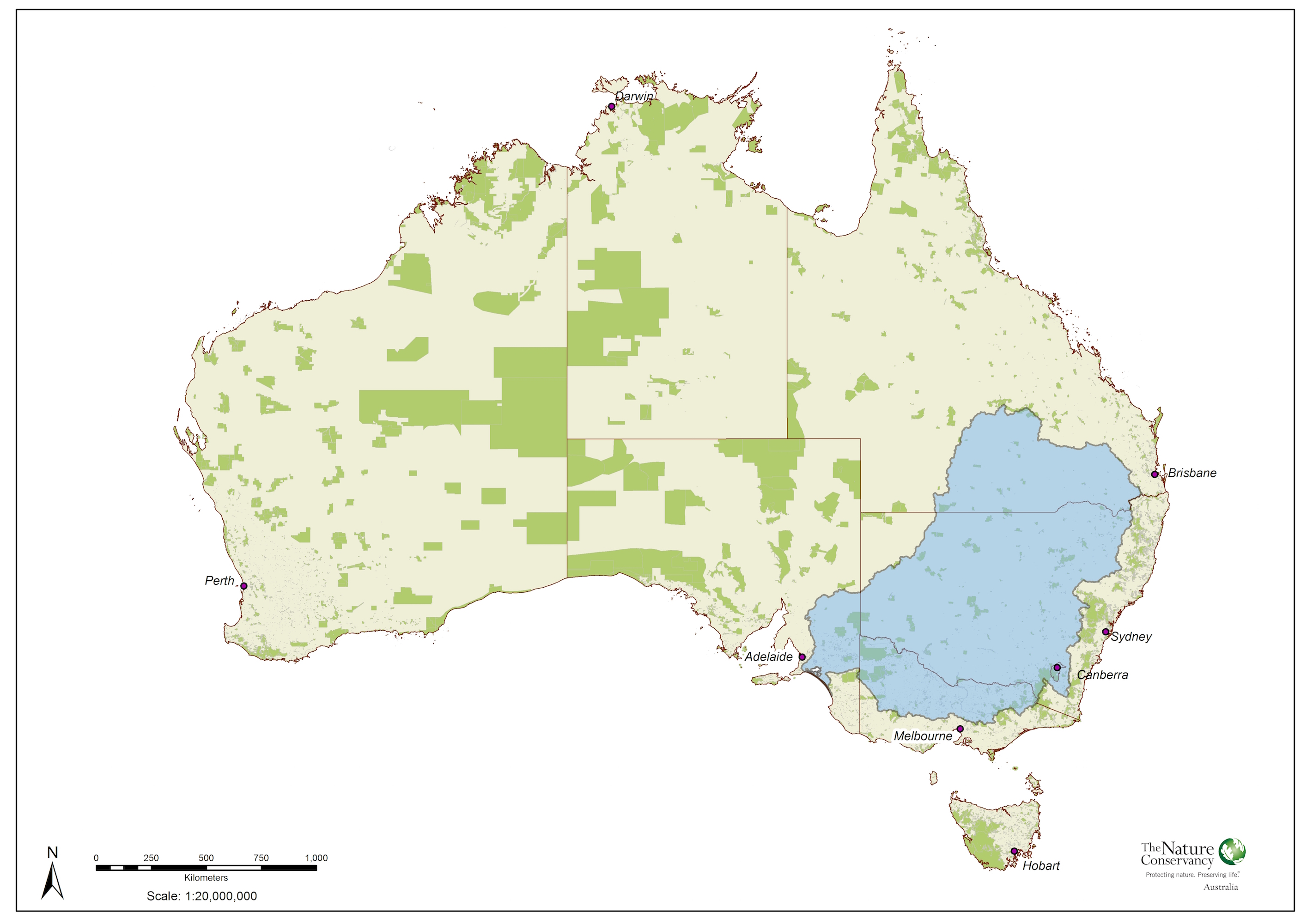

Australia’s agricultural industry is something of a paradox. Nearly two-thirds of the country’s land area is devoted to agriculture, generating 93 percent of the domestic food supply, as well as a US$31-billion-dollar export industry—despite the fact that Australia is the driest inhabited continent. Sustaining that level of agricultural activity in such an arid climate requires extensive irrigation from Australia’s river systems—a practice that’s had severe consequences for both farmers and rivers. With more and more water diverted for agriculture, some rivers were depleted to near exhaustion, wreaking havoc on the ecosystems they sustain. Farmers, meanwhile, having already pushed water sources to their limits, found themselves without water when droughts hit.

This overexploitation of water sources forced the Australian government to take action in the 1990s, putting a cap on water diversions and regulating use through the issuance of water entitlements. Entitlements give farmers and other users access to a specific annual water volume from the rivers and lakes, and can be bought, sold or leased through an open “water market,” not unlike stocks or commodities. For farmers, the water market offered a new way to obtain more water to sustain crops through dry seasons.

But for freshwater ecosystems, unfortunately, water entitlements were still over-allocated in some regions, including the Murray-Darling Basin, which drains one-seventh of the continent. In order to protect the rapidly degrading ecosystems in the basin, the national government bought back nearly 20 percent of the entitlements there off the market and diverted that water back to the environment.

The water buy-back was an extraordinary step, but it only came under enormous political pressure, and many of Australia’s wetlands are still badly depleted. And conservation groups and other water users have recognised that other countries are unlikely to take such a step at all. Now they’re asking, can markets be leveraged to return still more water back to ecosystems—not through government action, but through private investment?

Investment capital can be used to purchase water through markets—not just in Australia, but in many of the 37 water-scarce countries and multiple states in the western United States that show evidence of water trading. This type of investor-funded solution could secure a regular flow of water back to depleted ecosystems and sell the rest back to irrigators or cities on the open market—generating a material return for investors in the process.

Leveraging water markets

That’s the basic concept of a new conservation and impact investment model developed by The Nature Conservancy called Water Sharing Investment Partnerships (WSIP). “This model takes advantage of the motivations and incentives for trading water,” says Brian Richter, the lead scientist for the water program at The Nature Conservancy.

Quote: Brian Richter

As water assumes a value, it provides a huge incentive for water conservation and water savings.

While some aspects of the model will vary in each place it’s implemented, Richter says, the basic framework is this: WSIPs solicit investor capital, along with government grants and philanthropic donations, to acquire a portfolio of water rights. Most of those rights are then leased or sold back on the market, ensuring that farmers and cities have access to enough water and that investors see a financial return. But some portion of those rights are used to divert water back to natural ecosystems and to generate funding for ongoing ecological monitoring—something the Conservancy has never been able to do on a sustained scale.

The model, and strategies for its application, as well as other investor-funded solutions, are described in detail in the organisation's new report, "Water Share: Using water markets and impact investment to drive sustainability." (You can also read the Executive Summary here.)

The conceptual groundwork for WSIPs emerged from a conversation between Richter and Deborah Nias during an eight-hour drive through the Murray-Darling River Basin, surveying the extent of the ecological damage caused by water depletion. Nias is the CEO of the Murray Darling Wetlands Working Group, an Australian NGO working to restore and promote ecologically sound management of wetlands in the Murray-Darling Basin. Richter was researching a book on water scarcity, and Nias had agreed to show Richter around the basin.

“Our organisation was then at a crossroads where we needed to find some new way to finance what we were doing to return environmental water to wetlands,” Nias says. She and her colleagues had discussed the idea of establishing their own water trust into which people could donate water for environmental purposes, she says, “but the ever increasing value and cost of water meant this would be unlikely—certainly not at the volumes which we intuitively understood would be needed for a sustainable model.”

Richter suggested bringing in impact investors—those who want to see their money produce environmental and social benefits in addition to financial returns. Even conservative estimates suggest that potential funding might be several times greater than what conservation organizations could raise through philanthropy alone, thus allowing for a much greater environmental impact.

Richter has been working on water issues at The Nature Conservancy for nearly 30 years. His eyes light up when he talks about water scarcity, but he speaks with the precise, measured delivery of the college professor that he is. And the message he is delivering is bleak: Freshwater ecosystems are the most imperiled on the planet, and their condition is only getting worse. More than 30 percent of the water sources on our planet are being over-exploited, in many cases to near exhaustion. For Richter, impact investment might represent the last hope for freshwater conservation.

Quote: Brian Richter

Freshwater ecosystems are the most imperiled on the planet, and their condition is only getting worse.

Investing in conservation

While it’s difficult to estimate just how much investment the WSIP model will eventually attract, “we do know there’s a huge amount of interest, particularly from wealthy millennials, to have a more socially and environmentally conscious portfolio,” says Lauren Ferstandig, director of product development for NatureVest, The Nature Conservancy’s impact investment unit, which structured the deal. By having an impact investing unit dedicated to structuring conservation investments, the Conservancy has been able to build expertise across its investment work, tapping into a new source of capital and building the Conservancy's capacity to drive investment dollars to conservation.

“Some of those investors are happy to approach the investment holistically, taking into account environmental and social returns, as well as financial returns when they define success,” Ferstandig says. “With the WSIP model, investors have the opportunity to get in at the ground floor and learn about water investments that promote a conscientious use of water.”

But even purely profit-driven investors are seeing water as an appealing investment. Water trading is already common in Australia, not just among farmers but also among investors, for whom the transparent market and the growing disparity between supply and demand ensure that water remains a valuable commodity, says Cullen Gunn. Gunn is the director and CEO of Kilter Rural, a specialty fund that manages investments in farmland, water and ecosystem services in Australia, including the Murray-Darling Basin Balanced Water Fund—the Conservancy’s first WSIP. That fund, launched in late 2015, has now been capped at approximately US$20 million dollars, but it may soon reopen with a target of approximately US$76 million in the next four years.

The question, of course, is whether an investment-and-conservation strategy based on water markets can work in other parts of the world. The water market in Australia is well-established and their national government has set a precedent for buying water and returning it to the environment. Chile has a similar market system, with water rights granted by the national government, but few other markets are as transparent and flexible as Australia’s. Currently, 37 water-scarce countries around the world have some kind of system in which a central authority issues water rights—the most basic requirement for a water market—but many will require further regulation to make them run smoothly.

Water rights and trading in countries experiencing water scarcity

To that end, The Nature Conservancy has investigated several sites where the WSIP model could be adapted relatively easily. Latin America holds promise, and the Conservancy is also investigating feasibility in the western United States and northern Mexico, as well as other regions. If the WSIP model could be implemented in all the regions with water trading, and if the water assets were valued and traded similarly to those in Australia, the total market could be worth over US$331 billion, of which $13.4 billion might be actively traded in a given year.

The cost of water scarcity

Those are big numbers—but the scale of the global water crisis is even bigger. Half of all cities and three-fourths of irrigated farming areas in the world have experienced water scarcity, and as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has pointed out, water scarcity affects virtually every aspect of the world economy. Low water flows reduce the capacity of hydropower dams, resulting in price spikes or “brown outs.” Water-intense industries such as mining also suffer, as in Chile, where an ongoing drought has hampered production of copper. And low flows in rivers and reservoirs may also lead to declines in tourism activity, with ripple effects throughout local economies.

GIF: Water Supply Scarcity Over Time

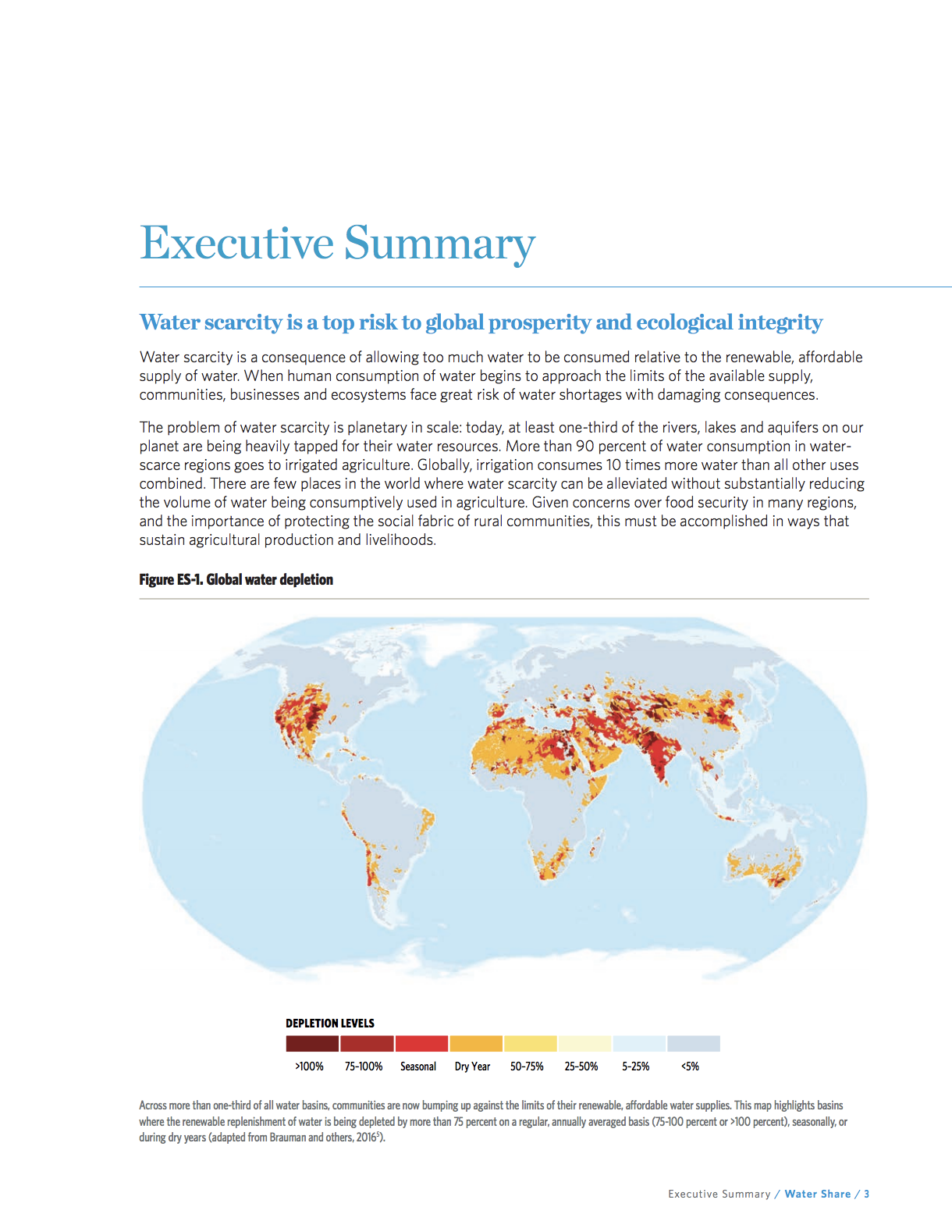

Some regions of our planet have been experiencing water scarcity for a very long time. This map illustrates the degree to which irrigated agriculture has depleted the renewable water supply. The “seasonal” category identifies areas where more than 75 percent of the water supply is depleted during certain months of the year, and “dry year” indicates areas where heavy depletion occurs during drought. (adapted from Brauman and others, 2016)

And as Richter points out, the ecological consequences are just as severe. One-third of all river and lake basins in the world are facing water scarcity. Major rivers like the Yellow River in China, the Indus River in Pakistan, and the Colorado and Rio Grande Rivers in the United States and Mexico are being completely depleted by human use at times—all their water has been diverted before the rivers reach the ocean.

Quote: Source: WWF International

76%: Estimated population decline in global freshwater species between 1970-2010.

For freshwater ecosystems, this is devastating. “As you start to deplete a river of its water, you don’t have to get far before you find detectable, measureable ecological consequences,” Richter says. The removal of water from ecosystems is a leading cause of imperilment for freshwater species; in rivers that see heavy diversions, populations quickly decline or are extirpated entirely. A recent report from WWF International estimates that global freshwater species populations declined by 76 percent between 1970 and 2010.

The Murray-Darling Basin offers a dramatic example of these consequences. Low water flows in some rivers have led to periodic blooms of toxic blue-green algae, which not only choke out fish and other aquatic life but also render the river unusable for human consumption or even irrigation in some cases.

“The further you dip into that bucket, the greater and greater those impacts become, till you don’t even have a river ecosystem,” Richter says.

More crop per drop?

In the past, most communities approached water scarcity from the supply side—drilling deeper in search of groundwater, or pumping water in from other basins. But in many regions there simply is no more water to be found, and new technologies like desalination aren’t cost-effective enough to reach the needed scale. The bottom line is that the global water supply will never increase enough, Richter points out—the only way to meet our ever growing demand for water is to be more efficient with how we use it.

We’ve already made some progress on water conservation, especially with urban uses. “Many cities are doing a great job of stabilising their water use,” Richter says, either through technological improvements like low-flow toilets, or through cultural changes, such reducing water use in gardening and landscaping. Some cities have managed to hold their water use steady for decades, despite fast-growing populations. But saving enough water to avert water scarcity on a global scale means looking to agriculture.

In the water-scarce regions of the world, more than 90 percent of all water consumed goes to farms. “That means that in most parts of the world, we cannot alleviate our water shortages if we can’t find ways to use less water on farms,” Richter says. “But, on the flip side, if we can find ways to save just a small percentage of the water used on farms, it will free up a great volume of water that can be used for other purposes, including restoring depleted rivers and lakes.”

This is the fundamental appeal of water markets—when water is valued as an asset, there is an incentive to use it more efficiently. If a farmer can produce the same crop yield with less water, he can sell his unused water for a profit. Farmers can get extra cash, cities can access more water for domestic uses, and conservationists can buy water and return it to the environment.

In the Australia water market, farmers are already buying and selling water regularly. In some cases, the market allowed farmers to maintain operations that might otherwise have been devastated by the Millennium Drought that gripped Australia from 1995 to 2010, says John Pettigrew, a retired fruit farmer who has sat on the board of several water authorities in Australia’s Goulburn Valley. Fruit growers were able to purchase the water they needed from dairy farmers, who in turn were able to purchase fodder for their stock or make other arrangements for their business.

Buying and selling water is fundamentally a business decision like any other, says Howard Jones, a grape farmer and chairman of the Murray Darling Wetlands Working Group. Farmers buy water to maintain high-value crops; they sell when they need capital, or when they’re retiring from farming. While some farmers might be drawn to the idea of selling to an environmental actor, he says, “first and foremost it’s about the cost of the water—few would quibble about where it goes.”

Still, transfer of water rights can be a politically fraught issue, and Richter is quick to stress that, in most cases, most of the water acquired in a WSIP model is returned back to the agricultural community. “It’s crucial to keep the farmers farming,” he says. “The primary purpose behind WSIPs is to move water back into the environment … But the secondary purpose is to help some of the water users who need more water for arguably good purposes, economically valuable purposes, gain access to some of that water they need.”

Quote: Lauren Ferstandig

With the WSIP model, investors have the opportunity to get in at the ground floor and learn about water investments that promote a conscientious use of water.

No one model for success

Because economic conditions and regulatory systems vary by country and even among states and smaller jurisdictions, the way WSIPs operate on the ground could look very different, even though the core purpose is the same, according to Ferstandig. In Australia, for example, most farmers are already using very water-efficient irrigation techniques—there are few improvements left to be made, so the only way to gain access to water is by purchasing the entitlements outright. That said, buying and selling water is a fairly simple process in Australia.

In the United States, on the other hand, it can be difficult to purchase water rights directly. Unlike Australia, or some countries in Latin America, “there isn’t a ‘water market’ where you can just go and buy water easily," Ferstandig says. “In some states water is tied to the land, and even when it’s not tied to the land there’s often a cultural belief that it should be, making farmers reluctant to sell water.” On the other hand, there is far more potential to improve the efficiency of agricultural water use in the United States. In other regions, she says, The Nature Conservancy may even consider buying land outright in order to access the accompanying water rights and manage that land in more water-efficient ways.

Different countries and regions also allow for different degrees of flexibility with the end use of water. In some countries and states, changing the use of a water entitlement from agriculture to conservation requires an extensive application process, while in other areas there are minimal regulations on end use. Because responding to continuing water shortages requires flexibility in the way water is moved and used, national and local governments need to be involved in WSIPs and other water-efficiency reforms.

“Everyone involved in water markets, particularly in North America, knows that policy is a huge part of the strategy,” Ferstandig says. “Even using philanthropy funds to buy water rights for the environment is really hard in some cases, and we need to make that easier.” Public policy can also play a role in ensuring that water markets remain equitable—as water use continues to rise, water rights will likely become even more expensive, and government intervention may be required to ensure that basic subsistence uses are met first, especially for indigenous groups who might otherwise be left out of the market system.

Modest government funding, along with philanthropy, might help attract investors to the WSIP model, too. Philanthropic capital plays an important role in both enabling conservation impact and de-risking these newer investment models for investors, who may be new to the water sector and the complexities of these transactions. And the more money that comes from government grants and philanthropy, Richter says, the more conservation outcomes WSIPs can generate while also creating a scalable, replicable model.

Water markets aren’t about easy money, Richter says. “You have to do things we didn’t have to do running on grants and donations. It opens another sphere of legal issues; it opens the issue of running a financial fund, having fund managers, soliciting investors. There’s no denying that it adds a layer of complexity—but if it can get us to ten times the impact, it’s worth doing.”

A future of freshwater conservation?

But the promise of the WSIP model and other innovative financial solutions, the part that makes Richter optimistic despite the obstacles, is this scale of funding—the potential to send millions of dollars’ worth of water back into natural ecosystems, while also helping to improve water and food security in water-stressed regions.

Richter witnessed this first hand in April, when the Murray Darling Wetlands Working Group helped usher a flow of environmental water into the Carrs, Capitts and Bunberoo Creeks wetland. Once a floodplain wetland within the Murray-Darling Basin, the region has been mostly dry for decades, cut off from regular floodwaters by a series of dams. That changed, as Richter says, “with the twist of a valve”—a series of siphons opened and, over a three-week period, nearly one billion liters of water flowed into the region.

It was a return to a once-annual ritual, imitating the spring rains spilling across the basin. During those floods, drought-stressed eucalyptus trees begin to perk up and native grasses reemerge. Fish eggs drift downstream and hatch in newly formed lakes and ponds. Frogs congregate there, too, adding their songs to those of the hundreds of thousands of birds that begin to arrive. It’s the kind of scene that Richter hopes we can make regular once more—we just have to make that investment in the future.

Make a Gift for Nature

Help us protect Australia's lands and waters for generations to come

Donate nowGlobal Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.